The UK’s first ever public gallery exhibition of works by Yun Hyong-keun (1928 – 2007), one of the leading figures of Korean art, will take place at Hastings Contemporary this summer.The UK’s first ever public gallery exhibition of works by Yun Hyong-keun (1928 – 2007), one of the leading figures of Korean art, will take place at Hastings Contemporary this summer.

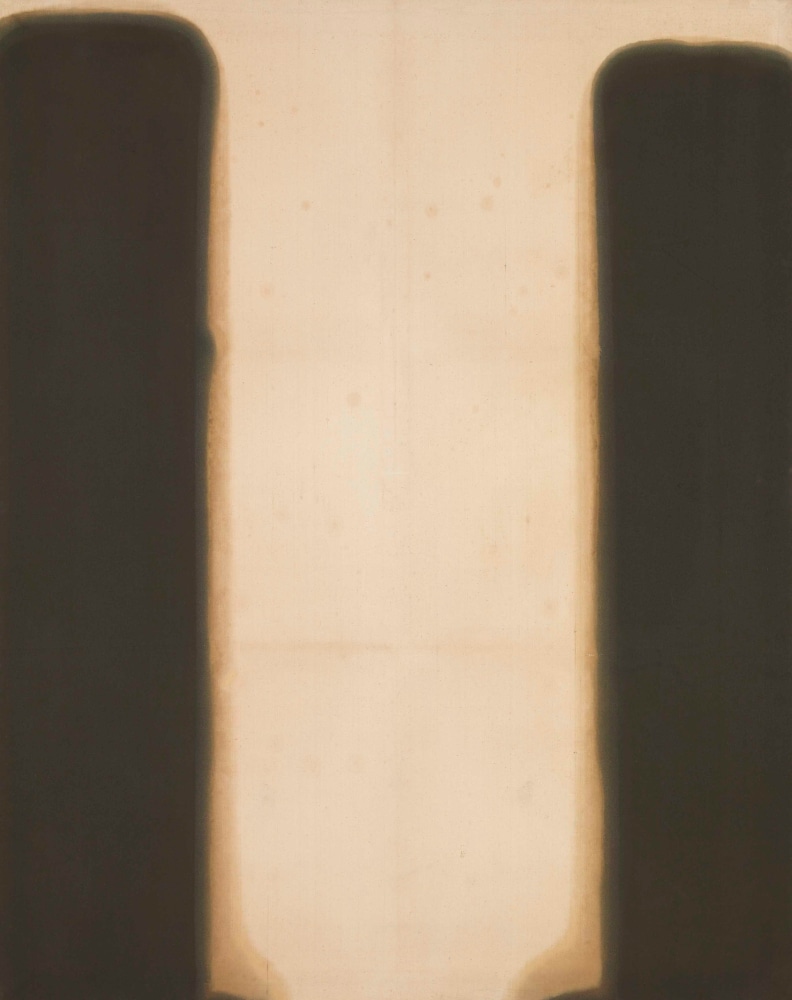

“The thesis of my painting is the gate of heaven and earth. Blue is the colour of heaven, while umber is the colour of earth. Thus, I call them ‘heaven and earth’, with the gate serving as the composition,” Yun once explained.

This is particularly relevant to Hastings Contemporary’s location, as the gallery is sited on the Old Town’s Stade, looking out onto the differing shades of blue of the expansive sky and sea. This is further reflected by the exhibition’s opening sequence of paintings; a small group of umber and ultramarine works from the early 1970s.

The show then continues by exploring the genesis of ‘the gate of heaven and earth’ with several works displaying its gradual widening until it almost disappears with the closing work – from the year of Yun’s death in 2007 – realised in Burnt Umber and Ultramarine Blue (1999 and 2007), in which ‘heaven’ is now almost completely suppressed by ‘earth’.

The concept of silence created by Yun’s work, particularly through the interpretation of gates or portals as voids, has the effect of turning the gallery space into a chapel or temple. The window onto the Old Town is veiled, as are the skylights, to enhance the meditative power of the individual paintings. This allows the viewer to be absorbed by the subtle range of tones, which on closer examination reveal the mix of ultramarine and umber through the blending of the two colours. And while the gate in each of the works from the 1970s absorbs the eye, the two late works Burnt Umber & Ultramarine Blue (1999 and 2007), with their narrowing portals place the emphasis back on earth, into which the artist himself would eventually be absorbed. As he said himself in 1990: “Since everything on earth ultimately returns to earth, everything is just a matter of time. When I remember that this also applies to me and my paintings, it all seems so trifling.”

In the aftermath of the Korean War (1950–1953), the country found itself effectively isolated from the rest of the world’s art markets and movements. This led South Korean artists to create their own sets of rules derived from the Korean tradition and creative parameters in the field of abstraction, with a group including Yun founding the Dansaekhwa movement.

From 1973, he began to establish a distinctive style of his own, with his work not only informed by nature but also by the scholar and calligrapher Chusa Kim Jeong-hui. He also engaged with Western art– such as his 2-year relocation to Paris with his family in the early 1980s and his encounter with Donald Judd (1928-1994) in 1991. He used these influences to create his signature palette of umber – the colour of the earth – and ultramarine – the colour of heaven – to create rectilinear compositions, reminiscent of traditional East Asian ink-wash paintings. Using pigment diluted with turpentine, Yun would spend days, weeks even months layering the paint down to create fields of intense darkness. This process effectively creates a physical sense of time, with the artist’s different returns to the canvas to layer more pigment resulting in blurred edges along its outer edges.

Although Yun went through the historical traumas in Korean history – the Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945), the Korean War, and the political turmoil during the postwar dictatorship – he never compromised with injustice, but stood against it. His anger and sadness, which inevitably follow the one who strives to remain truthful, can be easily seen in his early works. By the 1990s the boundaries between the monochrome sections had sharpened into hard edges with the more blackish umber and ultramarine mixture of paint dominating the plane of the canvas.

Although he is less well-known outside of his native South Korea, Yun Hyong-keun’s career and contribution to the Dansaekhwa movement during the sixties have begun to attract fresh interest internationally. His paintings’ combination of performative, rhythmic strokes, meditative qualities, and monochromatic aspects represent a contrast to Western Minimalism and works by artists such as Agnes Martin or Rothko’s Abstract Expressionism. A point the Hastings Contemporary show demonstrates, with Yun’s paintings reflecting his own culture while sparking comparisons with key artists in the canon of 20th century American and European abstraction.

Such was his impact, Yun’s work was referred to as Korean Minimalism, although he was somewhat modest. Responding to a question in 1976, he said: “What is painting? I still really don't know the answer. Is it a mere trace from combustion of life? I think one's ego is more freely and definitely expressed in the world of unconscious. The more one tries to express oneself, the ego becomes self-conscious, hence, the expression becomes contrived. Therefore, I don't think there can be answer to painting. I have no idea as to what I should paint, and at which point I should stop painting. There, in the midst of such uncertainty, I just paint. I don't have a goal in mind. I want to paint that something which is nothing, that will inspire me endlessly to go on.”

Liz Gilmore, Director says: “Our gallery, Hastings Contemporary, strives to show the very best of modern and contemporary art whilst also being one of the greenest galleries in the UK. The inspirational presence of Yun’s retrospective on the occasion of the 58th edition of the Venice Art Biennale gave momentum to our thinking and planning to bring Yun to Hastings. The exhibition will focus on Yun’s stunning and reflective umber and ultramarine paintings, which makes such a fitting juxtaposition with our location between land and sea.”

The exhibition is made possible with support by the Museum of Modern Art Korea, Tate, PKM Gallery, the estate of the artist, Korea Foundation and the British Korean Society.